Does evolution require species to reproduce different species?

A paper was published last month making the extraordinary claim that a species of ant produces offspring of two different species, their own and another one. While many people may think an ant is just an ant, there are in fact over 10,000 distinct species and, as I will explain in another essay, the divergence is high enough between the two species in question that this claim is analogous to saying that a chimpanzee has been witnessed to give birth to a human.

In this essay, instead of discussing the contents of the paper, I will discuss the general concept of species and especially if there’s any reason to expect, in the normal course of evolution, for individuals of a species to reproduce individuals of a different species. I will focus specifically on the contents of the actual paper in another essay.

Kind shall reproduce after its kind

The book of Genesis states multiple times that creatures reproduce “after their kind”1. As it happens, “creature” itself usually implies an animal in modern terms but originally referred something that was “created”, so I use it here to mean animals and plants. The 11th verse of the first chapter of Genesis is the first one in the book to make this point:

Then God said, “Let the earth sprout vegetation, plants yielding seed, and fruit trees on the earth bearing fruit after their kind with seed in them”; and it was so.

Moses, traditionally credited as the author, also points out that various types of animals reproduce after their kind in later verses. This is generally interpreted as meaning that organisms produce things similar to themselves. This seems reasonable and obvious enough. The world isn’t a chaotic mess with elephants producing gorillas, trees producing crabs, or bacteria producing velociraptors. Also, organisms are generally more similar to their parents than other conspecific organisms (i.e. organisms of the same species). However, organisms aren’t identical to their parents. One might ask then what the expected degree of similarity is. Or, how different can something be before it’s a different “kind”. I think it should go without saying that Moses did not intend to answer questions related to the modern science of systematics. Unfortunately, it was necessary for me to say that because there’s an entire pseudoscience called baraminology whose practitioners purport to be able to classify kinds in a precise scientific manner. Indeed, it’s often claimed that a kind is broad enough to constitute multiple species. Consequently, under this view, speciation (i.e. the evolution of different species) can occur but there is still some limit to the degree of possible evolution, and common ancestry of all life is well beyond this limit. Of course, it’s never clear exactly what the limit is. Genesis does not, nor does any other book of the Bible, posit any specific limit.

Creationists are not a monolith and not all hold to the idea that speciation is even possible. Indeed, many often caricature the theory of evolution as stating that an organism can literally give birth to a different species, which forms the basis of modern idioms like “Well, I’ll be a monkey’s uncle!” While it’s probably obvious, from my other essays, that I fundamentally disagree with these creationists about evolution, I’m not interested in cheap shots, of which there are plenty to be found on the internet. So let’s acknowledge this view is now less of a caricature. A particular group of evolutionary biologists, who also are not a monolith, are literally claiming that a species can reproduce a different species. As I said, I’ll tackle this specific claim in my next essay. For now, I’ll discuss how speciation generally happens and if it actually necessitates individuals of a species reproducing other species. It’s commonly stated that evolution is a gradual2 process so a species never just instantaneously becomes another one. This is true and creationists are often mocked for not understanding it. This is a bit unfair as it’s understandably difficult to actually wrap our — as a species — minds around this, in part because of the time scales involved. However, there’s also more basic conceptual difficulties involved with speciation in particular, which I’ll get to. I contend, perhaps controversially, that even most laymen who accept evolution as being true and most professional evolutionary biologists, who don’t specialize in speciation, fundamentally don’t understand how speciation works. However, in my opinion, the fundamentals of speciation are “known” in the sense that adequate and well-cited research has been done on them.

Why speciation doesn’t contradict the kind reproduces kind principle

Semantic issues

Firstly, there are multiple definitions of species used by different specialists. The fact that evolution is a gradual process, and the seemingly infinite capacity for disagreement within our species, suggests that there will never be universal agreement on this point. Therefore, it’s worth first pointing out that the answer to this section’s title is partly semantic. If, hypothetically, one claims that any living thing made up of atoms is the same species, then all living things are the same species. All bacteria and apes are now the same species so if a bacterium reproduces a gorilla this isn’t a mystery at all, they’re the same species! Obviously, this is silly. But this is the same issue with kinds described above. If kinds can’t be properly defined then it can’t be proven that bacteria and gorillas are different kinds, so a bacterium reproducing a gorilla wouldn’t necessarily contradict the kind reproduces kind principle. While Genesis didn’t define “kinds”, we can reasonably assume it’s intended meaning at least excludes this extreme scenario. To get more precise, it’s illustrative to see what happens if we map “kinds” to modern “species”.

The Biological Species Concept

Even though there’s numerous definitions of species some are more often used than others in the scientific literature by a wide margin. The most widely used one, often taught even in biology courses in schools, is the Biological Species Concept (BSC). This basically posits that if two organisms can’t reproduce with each other to generate a consistent lineage, they’re different species. For example, gorillas and elephants can’t reproduce with each other for multiple reasons, some more obvious than others. Donkeys and horses can reproduce with each other but produce sterile offspring. Therefore, they can’t generate a “consistent lineage” that would continue to reproduce its own lineage. The state of two species being unable to reproduce with each other and carry out a consistent lineage is called reproductive isolation3. This definition still leaves some ambiguity because, depending on the species in consideration, the causes of reproductive isolation can vary qualitatively and quantitatively. With regards to qualitative variation, this lay article has a decent summary. If two species are physically incapable of mating, maybe due to extreme size differences, we could say this is mechanical isolation. If two species are fully capable of mating and simply refuse on all occasions, this would be behavioral isolation. We can then see how there’s quantitative variation. Perhaps under behavioral isolation, individuals of one species will choose to mate with the other only 1% of the time. People can therefore endlessly debate what threshold is required to say two things are different species. Wu and colleagues put this well in an article debating the biological species concept:

The formation of species also progresses through the gradual transitions in various reproductive, behavioral, morphological and physiological characters, all of which are quantitative in nature. The statement that ‘two taxa are reproductively isolated’ is rather imprecise since RI (reproductive isolation) is not an on–off switch. If the F1 [hybrid] males between two taxa are 100% sterile and F1 [hybrid] females are 95% fertile, are the species reproductively isolated? This sort of half-way RI is the rule, rather than the exception, in most cases where the species status is not obvious

I don’t intend to debate whether or not the BSC is the “right” way to define species. I do think the concept has helped to inspire valuable research over the past century. Specifically, it has allowed researchers to quantify various modes of reproductive isolation and infer how they evolve. Reproductive isolation is a useful thing to study because it necessarily leads to reduction and eventually cessation of gene flow. This allows two species to diverge genetically and morphologically, which can then be used to differentiate them. Indeed, under some species concepts this would constitute the actual means of defining them as species, so reproductive isolation is important to speciation regardless of exact species definition.

How reproductive isolation evolves

How to conceive of reproductive isolation evolving

I’ve already mentioned that evolution is gradual and that this is difficult for people to intuit. This means speciation is also gradual and that’s also difficult to intuit. Using the BSC, the main conceptual difficulty here isn’t just the large time scales involved, it’s how two species change from not being reproductively isolated to being reproductively isolated. To use Wu and colleagues’ terms, when does the switch turn “on”? It was recognized even in the 1700s that reproductive isolation varied between 0 and 100%. Darwin, writing in the 19th century, praised the extensive plant breeding experiments of 18th century German botanists Kölreuter and Gärtner that documented this. In the chapter on “Hybridism” in the Origin of Species (paragraphs 85, 88-9 in Peckham’s Variorum Edition) Darwin wrote that

It has been already remarked, that the degree of fertility, both of first crosses and of hybrids, graduates from zero to perfect fertility…

From this absolute zero of fertility, the pollen of different species of the same genus applied to the stigma of some one species, yields a perfect gradation in the number of seeds produced, up to nearly complete or even quite complete fertility; and, as we have seen, in certain abnormal cases, even to an excess of fertility, beyond that which the plant’s own pollen will produce.

So in hybrids themselves, there are some which never have produced, and probably never would produce, even with the pollen of either pure parent, a single fertile seed: but in some of these cases a first trace of fertility may be detected, by the pollen of one of the pure parent-species causing the flower of the hybrid to wither earlier than it otherwise would have done; and the early withering of the flower is well known to be a sign of incipient fertilisation.

Nonetheless, he didn’t have a hypothesis on how this evolves. The problem took on a new form with the advent of Mendelian genetics, the discovery that inheritance of traits is related to discrete entities called genes. This allowed a reinterpretation of crossing experiments. If a researcher crossed a red plant and a blue plant, and the cross produces a blue plant, they’ve learned something about the factors behind coloration. Namely, that the gene — in modern terminology an allele — for one color (blue) overrides the other (red) even though both are present in the organism. So can one examine the genes causing reproductive isolation with crosses? Could one take two different species, cross them, and then look at the reproductive isolation genes in the offspring? A problem that immediately presents itself is that it’s necessarily impossible to cross species exhibiting complete reproductive isolation, and perhaps a headache to cross ones with partial reproductive isolation.

This also presents a problem conceptualizing how complete reproductive isolation could even evolve. I’ll illustrate the conceptual difficulty with an example where it could not evolve. Imagine there’s two species and the “reproductive isolation gene” has two alleles, A and a. The species are diploid so they have two alleles per genotype. One species has AA and the other has aa. If you cross the two then you get Aa but perhaps this is inviable, and so that explains why we have reproductive isolation between the species. So if there’s some ancestral species, with AA, how could aa ever evolve? As soon as one AA mutated into Aa, it would be inviable. Even if both alleles mutated simultaneously, which is much less probable, and the offspring went directly from AA to aa, this sole aa individual in its population would now be unable to mate with anything, as all crosses would make Aa. One would have to posit simultaneous mutations in multiple individuals in this particular gene, which is again extremely improbable4. Some readers may already question the scenario I’ve contrived. What if only 10% of Aa individuals are inviable, then could evolution of reproductive isolation happen? Maybe though that’s still a large fitness cost, suggesting it’d be difficult to bridge the gap between AA and aa5. This also is primarily applicable to issues of fertility, which constitute one form of reproductive isolation. Though we could imagine that a given behavior, the desire to mate with one species or the other, is governed by this single gene.

There is a verbal (non-mathematical) model that works around this called the Dobzhansky-Muller model. It’s almost a century old and well-known to speciation researchers, though I suspect not too well-known outside speciation research. I think the genius of it is still understated and it has extraordinarily wide applicability. The basic idea is that you can resolve the above issue by assuming that there are actually two genes that determine reproductive isolation, not one. It could be more than two but minimally it requires two. Although I’m attributing it to Dobzhansky and Muller this essential idea was realized by William Bateson6, who wrote in 1909 that

if the sterility of the cross-bred be really the consequence of the meeting of two complementary factors, we see that the phenomenon could only be produced among the divergent offspring of one species by the acquisition of at least two new factors; for if the acquisition of a single factor caused sterility the line would then end.

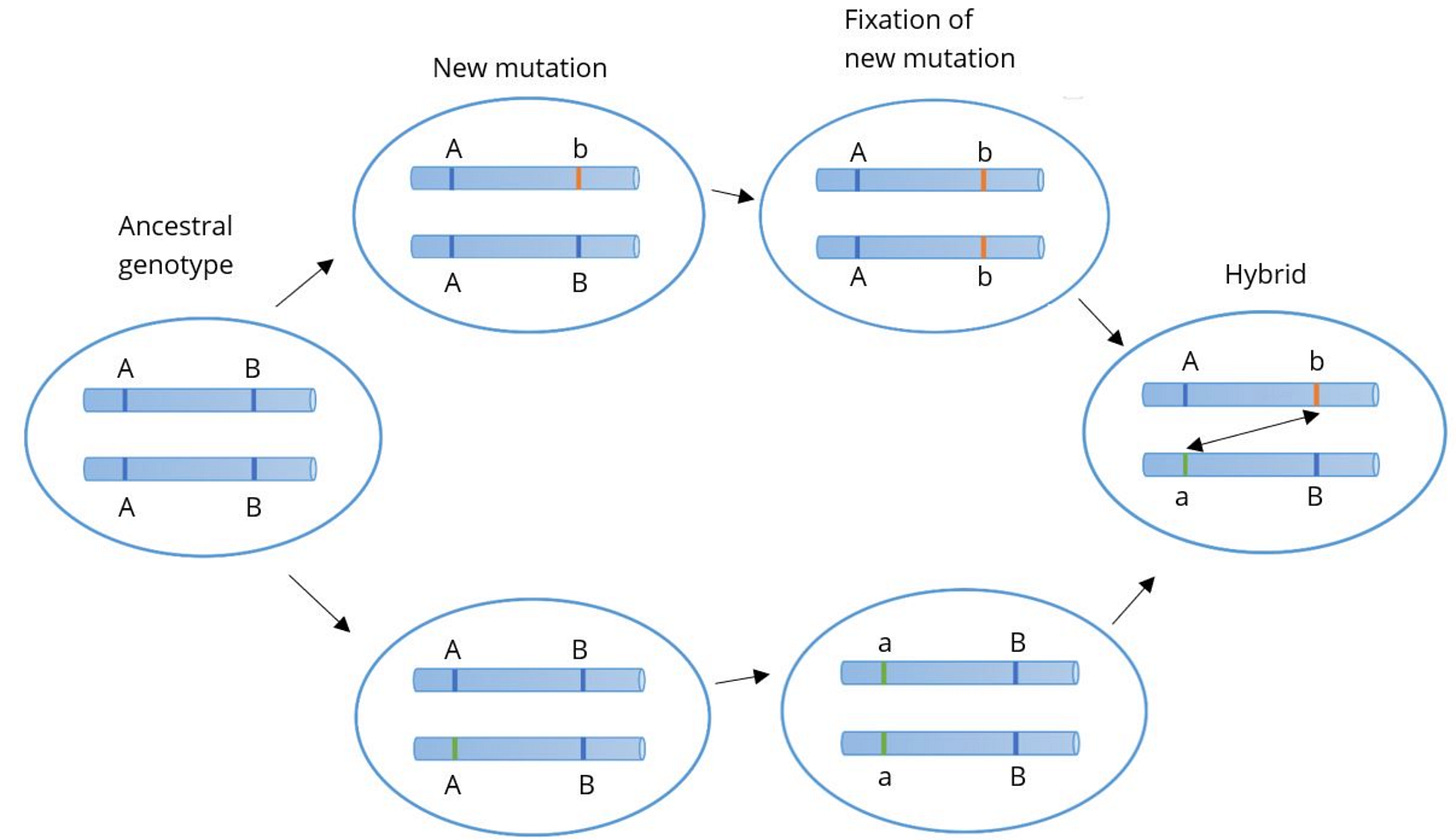

The main image from the linked Wikipedia article summarizes the Dobzhansky-Muller model as well as anything else.

Here, there are two genes each with two alleles. The two different letters (A and B) are the different genes and the capitalization signifies the different alleles within the gene (e.g. A and a). On the left there’s some ancestral species with AA and BB genotypes. As the figure moves right there’s a split into two different populations. One population has an A → a mutation and the other has a B → b mutation. Neither of these mutations is deleterious, so they stay within their respective populations. But if the populations interbreed, it produces a novel combination of genotypes, Aa and Bb. The issue here isn’t the existence of Aa or Bb, it’s that now a and b are together, where they never were before. If the combination of these two alleles causes reproductive isolation then that explains how the two species managed to evolve mutations causing reproductive isolation without suffering deleterious effects in their own populations. Interactions between genes that are qualitatively different from the action of either gene individually is often called epistasis. We can then just call this negative epistasis, meaning the epistatic interaction reduces fitness. I think if this model was more widely taught, it would help many overcome this conceptual difficulty.

We can finally tie this back to the principle of “kind reproducing after kind.” In the diagram above, there isn’t a single point in which a population gives rise to a population of a different species. Both the populations (top and bottom) are the same species as the ancestral population yet they are different species from each other. It seems to contradict basic principles of logic. Species A is the same as Species B and Species A is the same as Species C but Species B and C are different. This demonstrates the conceptual difficulty of dividing species rather than demonstrating that the model is illogical. Consequently, there isn’t necessarily any point in the speciation process where an individual organism reproduces an organism of a different species. Even if we equivocated “kinds” to “species under the biological species concept” it still can occur that kind reproduces after kind throughout the entire course of the Tree of Life. In this respect, Genesis fares well in the face of modern developments. Any perceived contradiction of the kind reproduces kind principle to known evolutionary mechanisms is a misconception. The kind reproduces kind principle arguably limits what can occur in a single reproduction event, but that doesn’t necessarily limit what changes can occur over multiple such events. Similarly, equivocating “kinds” to any other definition of species or any other taxonomic level wouldn’t present difficulties to the kind reproduces kind principle.

Is this really how it works?

It may then be asked if this is actually how reproductive isolation evolves in practice or if we can even know this. It’s admittedly difficult to demonstrate as, under the Dobzhansky-Muller model, the number of genes involved increases with genetic divergence7. Surely if we examined all the genes that prevent gorillas and elephants reproducing, it would be a lot more than two. So many in fact that it would be difficult to determine what all the relevant functions and interactions are. However, it is possible to identify plausible cases of this kind of incompatibility by examining closely related species, which presumably diverged recently. I can’t find a recent review paper that collects all such studies but one could just search Google Scholar to see such studies. I’ll also be self-aggrandizing and point out that the first paper from my PhD cites numerous such papers documenting specific examples in the first paragraph. Additionally, the Dobzhansky-Muller model isn’t the only one that has been conceived to explain the evolution of reproductive isolation. In a relatively recent preprint, Robert Unckless developed a model of the evolution of reproductive isolation through meiotic drive, where he also described known examples of reproductive isolation caused by meiotic drive as well as other proposed models.

I’ll conclude this essay by pointing out there are documented cases of reproductive isolation varying amongst populations in a gradual manner both in the lab and nature. A recent meta-analysis examined 34 distinct experiments that increased reproductive isolation between laboratory populations of fish, flies, beetles, nematodes, and chickens amongst other taxa (scientific names of all species examined are given in their Supplementary Table 3). The meta-analysis is based off of one conducted decades ago so the questions of interest were more specific than “can reproductive isolation evolve in a lab?” but it still serves as a nice compilation of studies that show the answer to this question is “yes”. They have appropriate caveats that 1) some of the cases examined were actually due to phenotypic plasticity, not evolution, and 2) the experiments don’t necessarily demonstrate what circumstances cause speciation in nature. The study still has sufficient data showing that reproductive isolation has been demonstrated to increase though evolution in some experiments.

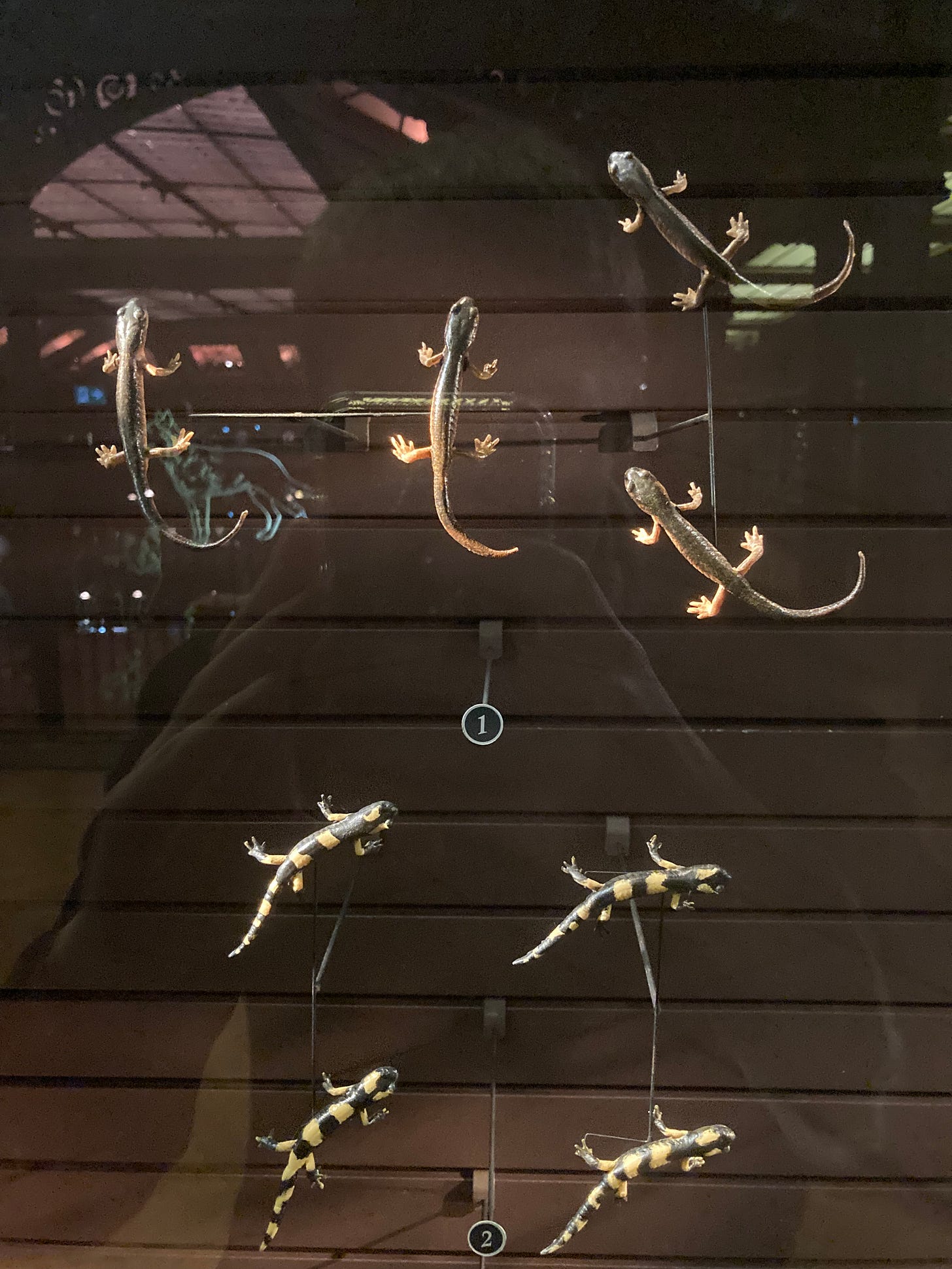

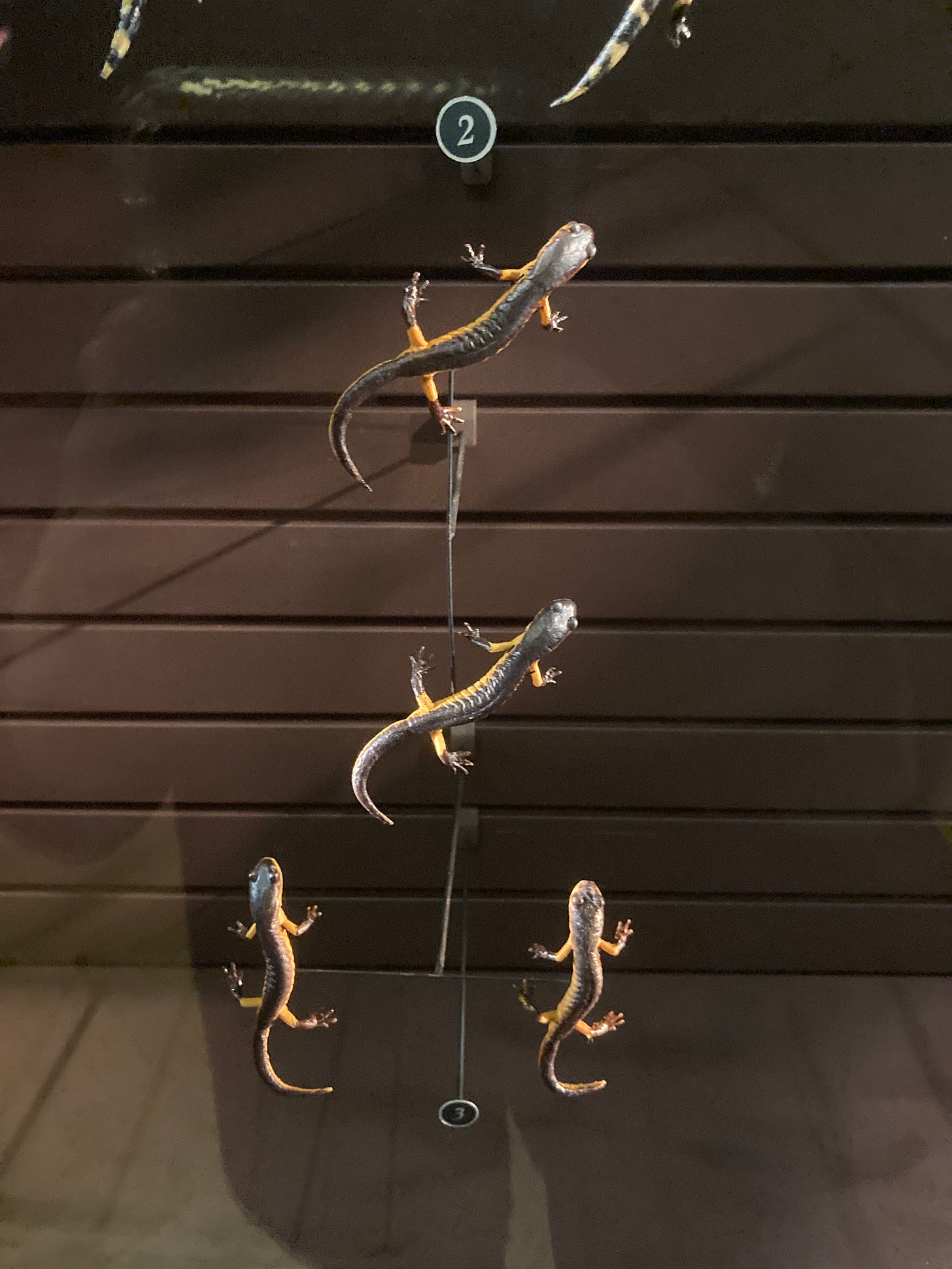

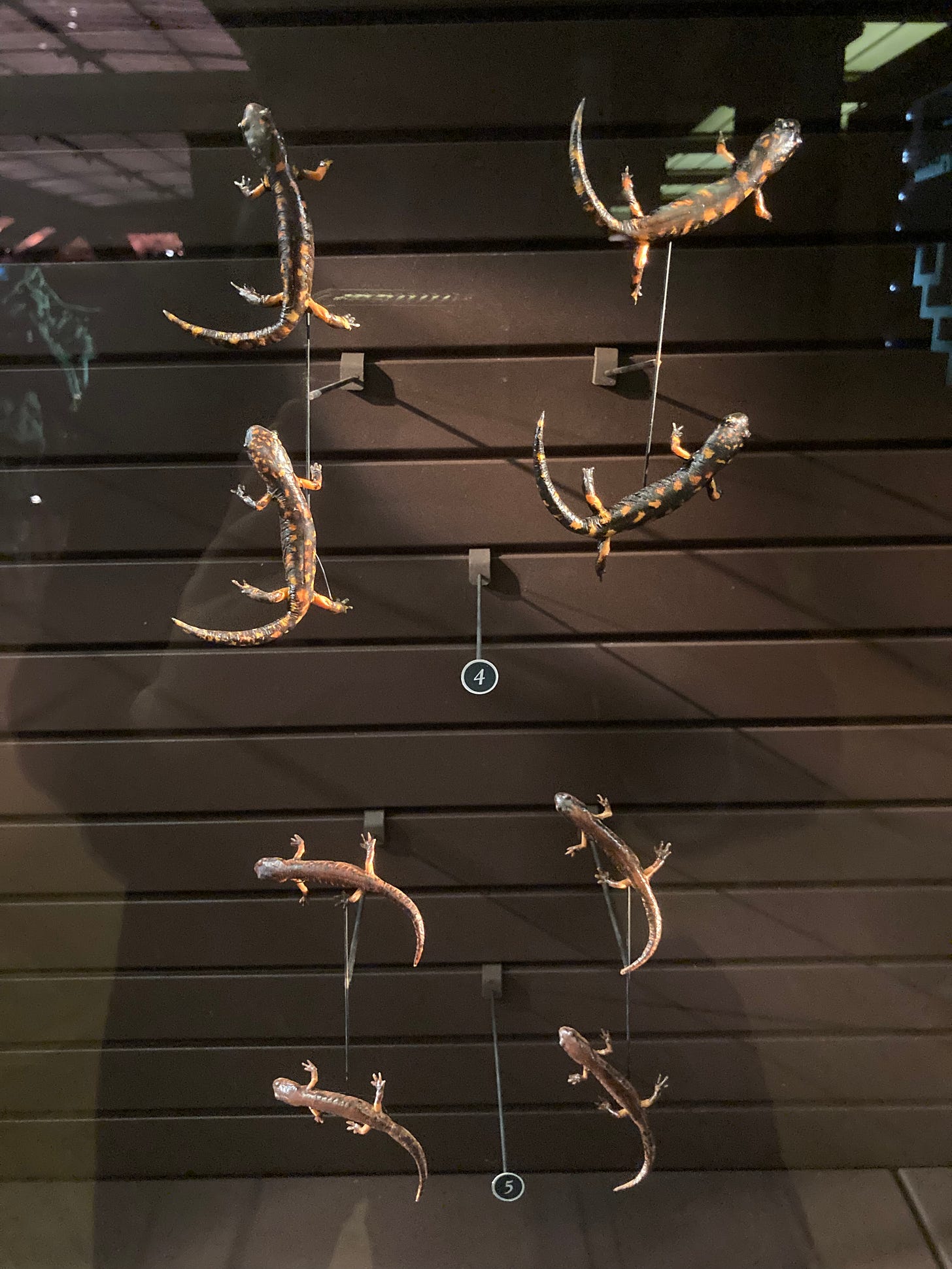

Examples of reproductive isolation varying amongst populations in the wild are “ring species”. This is a species for which there’s a chain (or “ring”) of interbreeding populations but the endpoints of the chain cannot interbreed. So even if we didn’t have a solid conceptual model of how this can occur, or evidence of the truth of the model, we would still be faced with the fact that there are demonstrable cases where 1) Species A and B can interbreed, and 2) Species A and C can interbreed, but 3) Species B and C can’t. A worthwhile one to read about are salamanders in the genus Ensantina, for which I have some low-quality phone pictures I took at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, France.

In many English translations that is. Incidentally, in some languages there are translations that use terms closer to the modern term for species. For example, the Louis Segond French translation uses the term “espèce”, which is the same term that would be used for “species” in scientific papers written in French. Similarly, a Portuguese translation uses "espécies” though a Spanish translation uses “genéro”, the same term as a “genus”.

Whether or not evolution is “gradual” runs into another semantic issue. The most obvious counterpoint to this claim is a theory called punctuated equilibrium. By “gradual” I mainly just want to convey that it forms a “genealogical continuum” as John Avise said here.

For this reason Wang and colleagues have proposed that the “Biological Species Concept” should actually be called the “Isolation Species Concept”. I’m inclined to agree with them because surely “biological” applies in some way or other to all species concepts, since species, in this context, are plainly biological entities. These debates aren’t about chemical species for example. Nonetheless, the term “Biological Species Concept” is so widely used I’m not pushing back here.

Computing this is quite simple if we know the necessary details, which would be difficult to obtain. A somewhat old article estimates the genome-wide average mutation rate in humans as being 2.5 x 10-8 per base pair per generation, which is still a reasonable estimate in light of newer data. It’s also a reasonable order of magnitude for many species. This means literally that for every one hundred million DNA base pairs in the human genome we would expect that on average 2.5 will mutate in someone’s offspring. Human cells have 3 billion such base pairs in total from each parent so the chances of a mutation happening at all, somewhere in the genome, are quite high. However, mutating a specific allele to another specific allele (e.g. A to a in the example here) is closer to the 2.5 x 10-8 number. Basically, if we grant this specific mutation has that probability, which is fairly low, the probability of the mutation happening twice (e.g. both alleles in a genotype or two separate individuals) is the square of that number, (2.5 x 10-8)2 = 6.25 x 10-16 which really stretches credulity. Positing even more mutations of course requires higher exponents.

This would be a kind of “underdominance”, in contrast to “overdominance” that I mentioned in a previous article. In that article I described a formula that computes the change in frequency of a given allele depending on its fitness effect. The model the formula is based on wouldn’t be perfectly applicable here if we assume the homozygotes have equal fitness but playing with that formula shows that even small fitness differences result in quick changes. In underdominance heterozygotes are expected to be quickly removed from a population, so the homozygote that was already the more common one would be favored.

The linked Wikipedia entry calls it the Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller model. This term came about from a paper by H. Allen Orr arguing for Bateson’s precedent. Though even Orr’s paper making this suggestion shows that Bateson did not grasp the full implications of this concept as well as Dobzhansky and subsequent historical evidence suggests Bateson conceived of speciation rather differently. This process is better analogized to speciation by sequence divergence, which makes it so some regions of the genome cannot recombine when hybridization occurs. Bateson’s view is discussed in detail in Chapter 28 of Cock and Forsdyke’s biography and critical analysis of Bateson. Based on my reading of Dobzhansky’s work (especially his most famous book) and Bateson’s paper my subjective evaluation is that Dobzhansky worked out the implications far more than Bateson did. I therefore purposefully keep the Dobzhansky-Muller designation, as I think it’s still common enough that pushback against the other term is still feasible.